Driving Towards Inclusive Futures: Insights from the Mobility Equity Workshop in London Ontario

On May 2023, SDG Cities London and Clean Air Partnership co-hosted a workshop with the Pillar team and other community members to learn more about Mobility Equity issues in London Ontario.

The event was part of the Vision Zero Hamilton Rd partnership between Pillar Nonprofit Network (SDG Cities), Crouch Resource Neighbourhood Centre, the City of London, and the HamRoad BIA using an SDG approach addressing systemic injustices in London Ontario related to urban mobility and accessibility, also informed by the work of Mobilizing Justice.

The partnership was created in response to the road violence episode last September 2022. An ongoing community engagement exposed what many of us already knew, a web of interrelated challenges including mobility poverty, unwelcoming public spaces, struggling local businesses, climate change, mental health issues, and social isolation.

This led to a community conversation on March 27, 2023, to discuss immediate steps to address current traffic-related safety concerns on Hamilton Road, propose their solutions, and take a look at more long-term solutions using the SDGs as a framework for action.

The opportunity to hear the community was valuable in itself. There were also a few short-term action items for the City of London and the Police to improve traffic in the area. Another outcome was the inclusion of mobility poverty in three different areas (housing, well-being, and mobility) of the 2023-2027 City Strategic Plan.

The most recent action related to this project was the workshop on May 23, an opportunity to build a better understanding of what mobility poverty is, what its inclusion in the strategic plan might represent for our communities, and what should be our next steps. The workshop was co-facilitated by Luis Patricio and two guest speakers: David Simor and Jennifer Geleff.

Among the people invited for the workshop we had Pillar staff and board members, representatives from the Transportation and Anti-Racism & Anti-Oppression Departments at the City of London, and other community members that are involved with issues intersecting mobility poverty including the Centre for Research on Health Equity and Social Inclusion, Crouch Neighbourhood Centre and London Cycle Link. Here are some highlights of the workshop.

Key concepts

The first part of the workshop presented some of the basic concepts around the theme and several data points about the reality in Canadian cities.

- Accessibility

In mobility equity, accessibility refers to a measure of the ease of reaching (and interacting with) destinations or activities distributed in space, around a city. It is used in a broad sense where every single equity aspect intersects with accessibility. The most relevant one is income, which is why mobility poverty was selected as the term to be included in the strategic plan. Gender and race issues are the other two main points included in this concept. Other aspects that play an important role in accessibility are age, immigrant status, number of children, and (dis)ability.

- Privilege

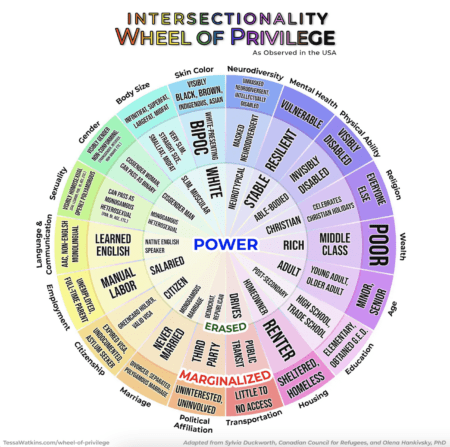

There is not a single best transportation mode or social group. They all have their advantages and shortcomings. To analyze accessibility, it is necessary to consider privilege as defined by the Intersectional Environmentalism movement.

“A set of unearned advantages, positive perceptions, and outcomes based on identity. Those who possess it are more likely to hold power both individually and as a group.”

Leah Thomas

During the workshop, we looked at privilege particularly related to motonormativity defined by researcher Ian Walker as “the cultural inability to think objectively and dispassionately about how we use cars.”

- Mobility Equity

Those two basic concepts lay the foundation to think about Mobility Equity. A concept that focuses on the equitable and just distribution of transportation services within communities, and explores how transport systems can systematically exclude, limit, and suppress people based on their intersectional identity and life conditions. These injustices are enabled by transportation practices and policies that fail to address the lived experiences of equity-deserving groups.

Here are a few real-life examples of how mobility equity issues might show up:

- Mobility Poverty: places that might only be accessible by modes of transportation that are not affordable

- Gendered Mobility: women who might be deterred from taking trips for fear of gender-based violence or due to trip patterns associated with gendered social constructs

- Racialized Mobility: non-white people who might feel unsafe or unwelcome in certain spaces

- Age: kids who are not allowed to move independently or seniors with limited mobility

- Immigrants: who might have challenges navigating a foreign environment or face barriers to obtaining a driver’s license.

Relevance of the problem

By establishing the link between mobility, and using accessibility as an intersectional concept to multiple equity aspects, we can have a clear picture of how mobility equity is an issue that has a significant detrimental effect on a large segment of the population.

- Near 20% of families in London, ON are lone-parent families. 81.5% of those are female lone parents (City Data and Community Profile 2022)

- Lone parents were less likely to be employed and more likely to be working in occupations that require relatively lower levels of education than those who were in a couple (Statistics Canada – Lone-parent families)

- 21.6% of London area residents are immigrants with permanent status. This figure doesn’t include refugees, people with student visas, or work permits (LFP, 2022).

- 18.8% of Londoners and 34.1% of lone-parent families in London(CMA) live below the LIM-AT threshold (Poverty Trends in London 2020 Report). Looking at disaggregated data, some of the disproportionately affected groups are visible minorities (35%), Indigenous (35,4%), immigrants that arrived in Canada between 6-10 years (35.9%), and the majority of newcomers (55.2%) (Poverty Trends in London 2020 Report).

Systems Thinking

The workshop included a few reflective practices where participants had an opportunity to share their perspectives and learn mobility injustice stories from real-world experiences collected over the project (and kept anonymous for privacy).

We discussed how mobility inequality can create barriers to accessing workplaces, and how people might feel “trapped” in their choices leading to situations like restricted/excessive travel or forced car use/ownership. Even how motorized traffic itself has contradicting impacts on residents and neighbourhoods (e.g.: bringing shoppers and visitors while bringing noise, population and danger).

That was a useful starting point to make new concepts more relatable. The final part of the workshop invited the participants to look at the bigger picture, considering how this is a systemic issue that goes beyond individual attributes such as personal choices or life conditions.

To help with this reframing, Paromit Nakshi wrote an insightful article on marginalized or vulnerable populations facing uneven mobilities. Paromit reminds us that those labels can be misleading in a few different ways, (I am)explicitly failing to recognize that those groups:

- are as capable or more capable than those with mobility privileges

- in many cases constitute a majority, or at least, a significant part of the population

- promote “othering” where separate (usually under-resourced) transportation infrastructures are created for the marginalized and

- systemic issues rather than individual characteristics as the cause for transport-related social exclusion.

Transportation planning was founded on the principle of equality with the noble goal to: “Provide unrestricted travel for all”. For anyone who has been working with equity, diversity, and inclusion, it is common knowledge that the provision of limited resources without acknowledging privilege in the design, implementation, and use of said resource is a recipe for injustice. Despite good intentions, we need a more nuanced approach.

The workshop was an excellent opportunity to lay some groundwork for creating a shared understanding of what mobility equity is and shed some light on how it can be addressed in the City’s new strategic plan. Some of the main takeaways from our session are that:

- a more efficient transportation network can be a more equitable one as well and

- even though mobility equity issues pervades our society, it is not a widely understood concept

Additional resource:

- Slide deck from workshop available here